Strategy Pattern in C++: A Flexible Approach to Dynamic Behaviors with Smart Pointers

This article demonstrates how to implement the Strategy Pattern in C++, using a simple example of ducks with different flying and quacking behaviors. It highlights the flexibility and reusability of the pattern and shows how smart pointers can be used to manage memory safely and prevent leaks.

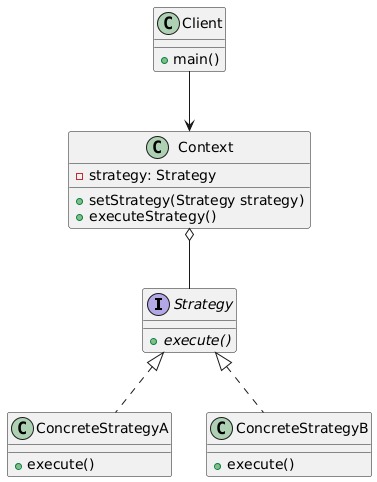

Strategy Design Pattern

Overview

The Strategy design pattern is a behavioral design pattern that enables selecting an algorithm’s behavior at runtime. It defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one in a separate class, and makes them interchangeable without altering the client code. This pattern promotes the Open-Closed Principle, allowing the addition of new strategies without modifying existing ones. It typically consists of three main components: the Context, which uses a Strategy object; the Strategy interface, which defines a common contract for all algorithms; and the Concrete Strategies, which implement specific variations of the algorithm. The Strategy pattern is particularly useful when a class must support multiple behaviors that can vary independently of the clients using them.

Key Components

Context a. Role: Acts as the primary class that interacts with clients and uses a Strategy object to perform specific behaviors. b. Responsibility: Maintains a reference to a Strategy object and delegates the algorithm’s execution to it. c. Flexibility: Can switch between different Strategy objects at runtime, enabling dynamic behavior changes.

Strategy Interface a. Role: Serves as a common contract for all concrete strategy implementations. b. Responsibility: Declares a method (or methods) that all concrete strategies must implement. c. Purpose: Ensures consistency and allows the Context to work with any Strategy implementation interchangeably.

Concrete Strategies a. Role: Provide specific implementations of the algorithm defined in the Strategy interface. b. Responsibility: Implement different variations of the algorithm, encapsulating their details. c. Purpose: Allow easy addition of new behaviors without modifying the Context or other strategies, adhering to the Open-Closed Principle.

Example: Strategy Design Pattern in Action

Let’s consider an example to understand the Strategy design pattern in action. We will design a Duck class that can exhibit different behaviors, such as flying and quacking. Instead of hardcoding these behaviors into the Duck class, we will use the Strategy pattern to encapsulate these behaviors into separate interfaces and classes. This approach allows us to dynamically change the behavior of a Duck at runtime and ensures flexibility and adherence to the Open-Closed Principle.

Here’s a step-by-step explanation and implementation of the pattern:

1. Duck Class

The Duck class represents the context in the Strategy pattern. It uses composition to include flying and quacking behaviors via iFlyBehavior and iQuackBehavior interfaces. Behaviors can be swapped dynamically using setter methods.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

#pragma once

#include "ifly_behavior.hpp"

#include "iquack_behavior.hpp"

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

namespace duck {

class Duck {

public:

virtual ~Duck() = default;

Duck(const Duck &) = delete;

Duck(Duck &&other) noexcept

: m_flyBehavior(std::move(other.m_flyBehavior))

, m_quackBehavior(std::move(other.m_quackBehavior)) {}

Duck &operator=(const Duck &) = delete;

Duck &operator=(Duck &&other) noexcept {

if (this != &other) {

m_flyBehavior = std::move(other.m_flyBehavior);

m_quackBehavior = std::move(other.m_quackBehavior);

}

return *this;

}

void swim() const { std::cout << "I'm swimming.\n"; }

virtual void display() = 0;

void performQuack() { m_quackBehavior->quack(); }

void performFly() { m_flyBehavior->fly(); }

void setFlyBehavior(std::unique_ptr<iFlyBehavior> flyBehavior) {

m_flyBehavior = std::move(flyBehavior);

}

void setQuackBehavior(std::unique_ptr<iQuackBehavior> quackBehavior) {

m_quackBehavior = std::move(quackBehavior);

}

protected:

Duck() = default;

std::unique_ptr<iFlyBehavior> m_flyBehavior;

std::unique_ptr<iQuackBehavior> m_quackBehavior;

};

}

2. Behavior Interfaces

The interfaces iFlyBehavior and iQuackBehavior define the contracts for flying and quacking behaviors. All concrete behaviors will implement these interfaces.

Fly Behavior Interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#pragma once

class iFlyBehavior {

public:

virtual ~iFlyBehavior() = default;

virtual void fly() = 0;

};

Quack Behavior Interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#pragma once

class iQuackBehavior {

public:

virtual ~iQuackBehavior() = default;

virtual void quack() = 0;

};

3. Concrete Behaviors

Concrete classes provide specific implementations of flying and quacking behaviors.

Concrete Fly Behaviors:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

#include "ifly_behavior.hpp"

#include <iostream>

class FlyWithWings : public iFlyBehavior {

public:

void fly() override {

std::cout << "I'm flying with wings!\n";

}

};

class FlyNoWay : public iFlyBehavior {

public:

void fly() override {

std::cout << "I can't fly.\n";

}

};

class FlyRocketPowered : public iFlyBehavior {

public:

void fly() override {

std::cout << "I'm flying with a rocket!\n";

}

};

Concrete Quack Behaviors:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#include "iquack_behavior.hpp"

#include <iostream>

class Quack : public iQuackBehavior {

public:

void quack() override {

std::cout << "Quack!\n";

}

};

class MuteQuack : public iQuackBehavior {

public:

void quack() override {

std::cout << "...\n";

}

};

4. Duck Subclasses

Specific types of ducks inherit from the Duck class and define their own display behavior.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

#include "duck.hpp"

#include "fly_with_wings.hpp"

#include "quack.hpp"

namespace duck {

class MallardDuck : public Duck {

public:

MallardDuck() {

m_flyBehavior = std::make_unique<FlyWithWings>();

m_quackBehavior = std::make_unique<Quack>();

}

void display() override {

std::cout << "I'm a Mallard Duck.\n";

}

};

class ModelDuck : public Duck {

public:

ModelDuck() {

m_flyBehavior = std::make_unique<FlyNoWay>();

m_quackBehavior = std::make_unique<Quack>();

}

void display() override {

std::cout << "I'm a Model Duck.\n";

}

};

}

5. Client Code

The main function demonstrates how to use the Strategy pattern. It creates ducks, displays their behaviors, and dynamically changes their flying behavior using setFlyBehavior.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

#include "mallard_duck.hpp"

#include "model_duck.hpp"

#include "fly_rocket_powered.hpp"

int main() {

duck::MallardDuck myDuck;

myDuck.display();

myDuck.performQuack();

myDuck.swim();

myDuck.performFly();

duck::ModelDuck modelDuck;

modelDuck.display();

modelDuck.performFly();

modelDuck.performQuack();

modelDuck.swim();

auto rocketPoweredFly = std::make_unique<duck::FlyRocketPowered>();

modelDuck.setFlyBehavior(std::move(rocketPoweredFly));

modelDuck.performFly();

return 0;

}

Explanation of the Client Code:

Create Ducks:

The client creates aMallardDuckand aModelDuck. These ducks are initialized with default flying and quacking behaviors.Display Behaviors:

Each duck displays its type and performs its default behaviors by callingperformFly()andperformQuack().Dynamic Behavior Change:

TheModelDuckchanges its flying behavior to rocket-powered flight at runtime using thesetFlyBehavior()method. Afterward, it performs the updated flying behavior.

This example illustrates how the Strategy design pattern enables flexibility by separating the behaviors (flying and quacking) from the core Duck class. Using composition, the Duck class can dynamically change behaviors at runtime. Additionally, we used smart pointers to manage memory safely and avoid potential memory leaks, leveraging modern C++ practices for robust design.

Conclusion

The Strategy Pattern provides an elegant solution for managing algorithms and behaviors in a flexible, reusable, and maintainable way. By encapsulating behaviors in separate classes and leveraging composition, we can easily extend or modify an object’s behavior without altering its underlying code. In this example, we showcased how ducks can have different flying and quacking behaviors, demonstrating the versatility of the pattern. Additionally, we utilized smart pointers to manage the dynamic allocation of strategy objects, ensuring memory safety and preventing potential memory leaks. This approach highlights how modern C++ features can enhance traditional design patterns.